A galaxy is a gargantuan collection of stellar and interstellar matter—stars, gas, dust, neutron stars, black holes—isolated in space and held together by its own gravity. Astronomers are aware of literally millions of galaxies beyond our own. The particular galaxy we happen to inhabit is known as the Milky Way Galaxy, or just the Galaxy, with a capital G.

Our Sun lies in a part of the Galaxy known as the Galactic disk—an immense, circular, flattened region containing most of our Galaxy's luminous stars and interstellar matter (and virtually everything we have studied so far in this book). We do not need sophisticated astronomical equipment to verify this statement. Our own unaided eyes will suffice. Figure 23.1 illustrates how, viewed from within, the Galactic disk appears as a band of light stretching across our night sky, a band known as the Milky Way. As indicated in the figure, if we look in a direction away from the Galactic disk (red arrows), relatively few stars lie in our field of view. However, if our line of sight happens to lie within the disk (white and blue arrows), we see so many stars that their light merges into a continuous blur.

Figure 23.1 Gazing from Earth toward the Galactic center (white arrow), in this artist's conception, we see myriad stars stacked up within the thin band of light known as the Milky Way. Looking in the opposite direction (blue arrow), we still see the Milky Way band, but now it is fainter because our position is far from the Galactic center, with the result that we see more stars when looking toward the center than when looking in the opposite direction. Looking perpendicular to the disk (red arrows), we see far fewer stars. The inset is an enhanced infrared satellite view of the sky all around us; the white band is the disk of our Milky Way Galaxy, which can be seen with the naked eye from very dark locations on Earth.

Paradoxically, although we can study individual stars and interstellar clouds near the Sun in great detail, our location within the Galactic disk makes deciphering our Galaxy's large-scale structure from Earth a very difficult task—a little like trying to unravel the layout of paths, bushes, and trees in a city park without being able to leave one particular park bench. In some directions the interpretation of what we see is ambiguous and inconclusive. In others, foreground objects completely obscure our view of what lies beyond, but we cannot move around them to get a better look. As a result, astronomers who study the Milky Way Galaxy are often guided in their efforts by comparisons with more distant, but much more easily observable, systems.

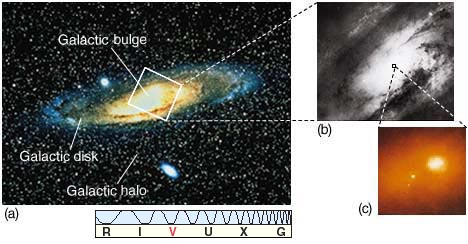

Figures 23.2 and 23.3 show three galaxies thought to resemble our own in overall structure. Figure 23.2 is the Andromeda Galaxy, the nearest major galaxy to the Milky Way Galaxy, lying about 900 kpc (nearly 3 million light years) away. Andromeda's apparent elongated shape is a consequence of the angle at which we happen to view it. In fact, this galaxy, like our own, consists of a circular galactic disk of matter that fattens to a galactic bulge at the center. The disk and bulge are embedded in a roughly spherical ball of faint old stars known as the galactic halo. These three basic galactic regions are indicated on the figure (the halo stars are so faint that they cannot be discerned here; see Figure 23.10). Figure 23.3(a) and (b) shows views of two other galaxies—one seen face-on, the other edge-on—that illustrate these points more clearly.

Figure 23.2 (a) The Andromeda Galaxy probably resembles fairly closely the overall layout of our own Milky Way Galaxy. The disk and bulge are clearly visible in this image, which is about 30,000 pc across. The faint halo stars cannot be seen. The white stars sprinkled all across this image are not part of Andromeda's halo; they are foreground stars in our own Galaxy, lying in the same part of the sky as Andromeda, but about a thousand times closer. (b) More detail within the inner parts of the galaxy. (c) The galaxy's peculiar—and still unexplained—double core; this inset covers a region only 15 pc across.

Figure 23.3 (a) This galaxy, catalogued as NGC, and seen nearly face-on, is somewhat similar in its overall structure to our own Milky Way Galaxy and Andromeda. (b) The galaxy NGC 891 happens to be oriented in such a way that we see it edge-on, allowing us to see clearly its disk and central bulge.